Why remote access to cloud infrastructure is harder than it looks

When everything moved to “the cloud”, most companies quietly kept one very old habit: putting a VPN in front of everything and calling it a day.

That worked when:

– 90% of people were in the office

– apps lived in one or two data centers

– “remote access” meant a few salespeople on laptops

Today it’s the opposite:

– people connect from anywhere, on any device

– infrastructure is spread across AWS, Azure, GCP, SaaS and on‑prem

– attackers actively hunt for VPNs and exposed portals

So “segurança acesso remoto infraestrutura cloud” is no longer about a tunnel. It’s about minimizing what a user can see, even if they are inside your network, and tying every action to a verified identity and device.

We’ll go through three pillars:

– VPN (classic approach)

– ZTNA (Zero Trust Network Access)

– federated identity

And then I’ll suggest a few non‑obvious tricks that go beyond “just buy product X”.

—

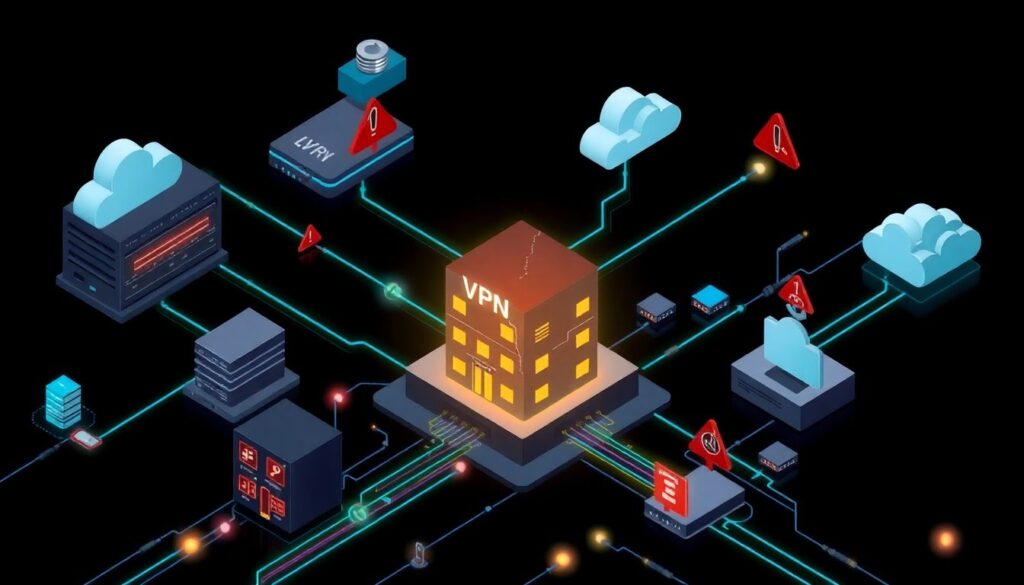

VPN: why the old workhorse is getting dangerous

VPN still isn’t dead. It’s everywhere, especially in hybrid environments with legacy systems. But the way many companies use VPN turns it into a single, fat point of failure.

The real‑world problem with “big flat VPNs”

A very common pattern in mid‑size companies:

– One main VPN gateway (or two for HA)

– After connecting, employees can see most of the internal network

– Access control is done with IP ranges and firewall rules

– Authentication is often “username + password + maybe SMS”

This is attractive to attackers. Why?

– A VPN portal is a perfect phishing target

– VPN exploits are published and weaponized quickly

– Once a compromised account connects, lateral movement is easy

Between 2019–2023, multiple high‑profile breaches (e.g., Colonial Pipeline, several ransomware campaigns) started with stolen or brute‑forced VPN credentials combined with missing MFA or unpatched gateways.

In other words, a classic VPN tends to expand trust: once inside, you’re “one of us”.

—

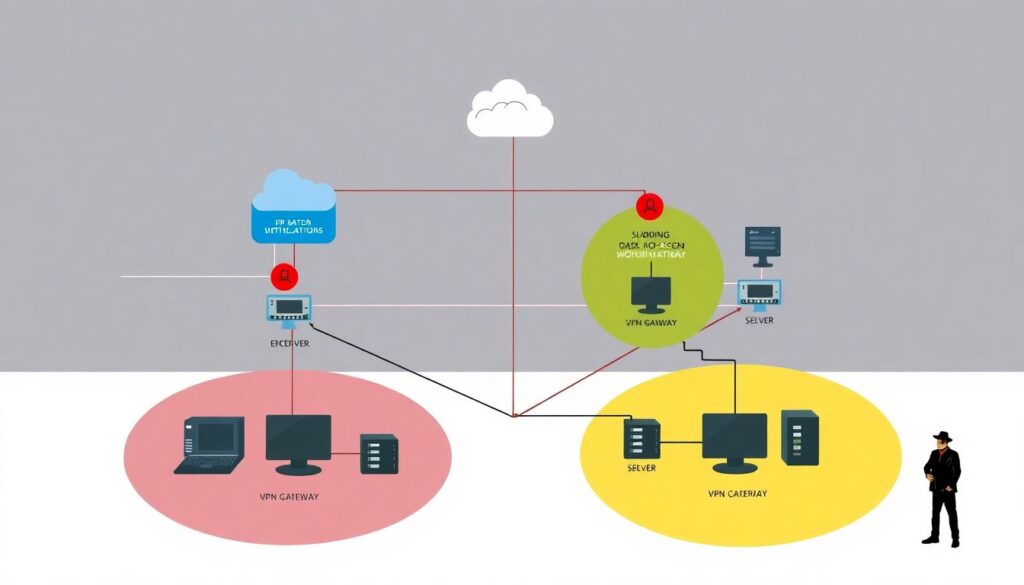

Technical deep‑dive: what a VPN actually does

From a network perspective, a VPN typically:

– Creates an encrypted tunnel (usually IPsec or TLS‑based)

– Assigns a virtual IP from a pool

– Injects routes so the client can reach internal networks

– Relies on network‑level ACLs and firewalls to restrict access

This model is *location‑centric*: if traffic comes from a “trusted” network or VPN IP pool, it’s assumed good enough, unless explicitly blocked.

The big issue: internal services usually cannot distinguish which user is connecting unless you build separate layers of auth. That’s one reason VPN alone is brittle in modern “segurança acesso remoto infraestrutura cloud”.

—

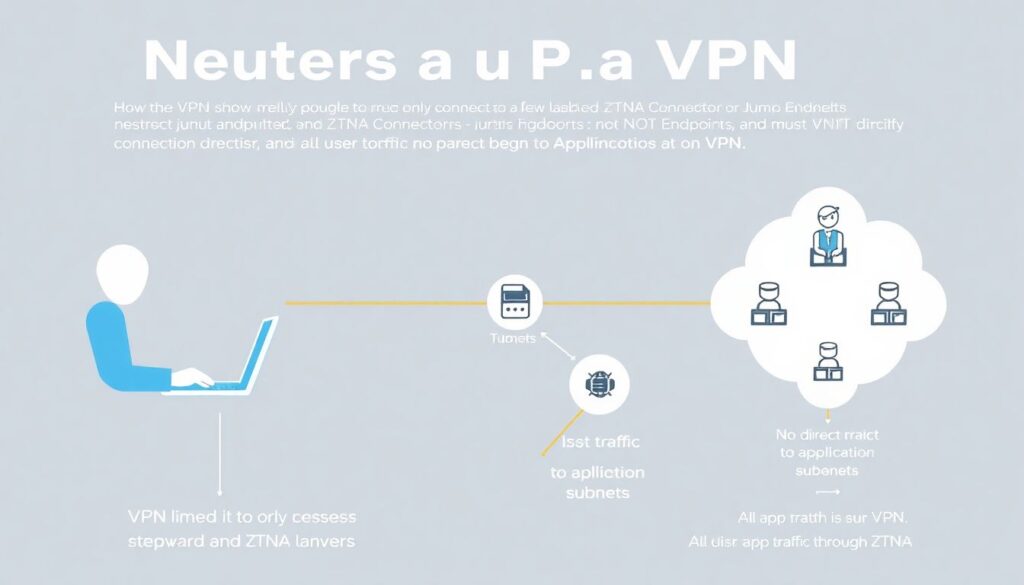

ZTNA: putting a bouncer in front of every app

Zero Trust Network Access flips the old idea. Instead of:

> “Give user a tunnel, then let the network decide”

It goes:

> “User, device, and context are checked *per application*, and the network stays dark.”

In practice, ZTNA works more like a smart reverse proxy than a VPN.

How ZTNA changes the game

A typical ZTNA flow:

1. User authenticates to an identity provider (IdP) with MFA.

2. A ZTNA broker checks:

– who the user is (groups, role, risk score)

– device posture (managed/unmanaged, OS, patches)

– context (geo, time, behavior anomalies)

3. Broker exposes *only* specific apps or services to that user.

4. The rest of the network remains invisible (no port scans, no guessing).

This is why many teams search for the “melhor ztna para substituir vpn corporativa”: the goal is not just “tunnel vs no tunnel”, it’s granular, per‑app access with strong identity at the core.

—

Technical details: under the hood of ZTNA

Common building blocks of soluções vpn ztna para empresas:

– Connectors / agents

Small components deployed near the protected apps (in VPCs, data centers, Kubernetes clusters).

They establish outbound connections to the ZTNA cloud, so you don’t open inbound firewall ports.

– Application‑level policies

Rules like:

– “DevOps group → SSH to bastion in AWS only from managed devices”

– “Finance group → only HTTPS to billing app, no RDP anywhere”

– Identity integration

ZTNA enforces decisions using SAML/OIDC claims from your IdP; the network doesn’t rely on IP alone.

– Transport

Often TLS over port 443, sometimes with mutual TLS between connector and ZTNA broker.

Result: attacker with stolen credentials but no compliant device, or no matching risk profile, is blocked or heavily restricted.

—

Real‑world example: shrinking attack surface in a week

A 500‑person tech company had:

– a single VPN

– a “flat” internal network shared by dev, finance, and HR

– dozens of cloud services reachable over the VPN

Pentest found:

– VPN portal vulnerable to password spraying

– once inside, an attacker could ping or port‑scan 70%+ of internal hosts

They didn’t have time to re‑architect the entire network. So they did something pragmatic:

1. Kept the VPN for some legacy use, but:

– moved all new apps behind a ZTNA broker

– configured ZTNA as the *primary* way to reach cloud services

2. Split‑tunneled access intelligently:

– Office 365, public SaaS → direct to internet

– admin panels, internal APIs → ZTNA only

3. Tightened identity:

– enabled phishing‑resistant MFA for admins

– required device checks for devs accessing production

Within a week:

– port‑scanning from a compromised VPN account saw almost nothing valuable

– 80% of day‑to‑day work no longer relied on the legacy VPN at all

Instead of a big‑bang “kill the VPN” project, they slowly moved gravity toward ZTNA.

—

Federated identity: glue between cloud, VPN, and ZTNA

So far we’ve talked about how traffic flows. Now let’s talk about who is behind that traffic.

Identity is the anchor for modern serviços de segurança em acesso remoto cloud. Without it, you end up with:

– separate credentials for VPN, cloud consoles, internal apps

– inconsistent MFA

– no centralized view of user risk

That’s where “identidade federada na nuvem para acesso remoto” becomes essential.

What federated identity actually solves

Federated identity means:

– One authoritative identity (e.g., Azure AD, Okta, Google Workspace, Keycloak)

– Apps, VPNs, and ZTNA don’t store passwords; they trust assertions (SAML / OIDC tokens) from that IdP

– Access decisions use identity attributes: groups, roles, risk level, device info

Benefits:

– One place to enforce MFA and password policies

– One place to revoke access (offboarding in minutes, not weeks)

– Easier audit and compliance: who accessed what, and when

This turns identity into your primary security perimeter, not the physical network.

—

Technical details: using identity to drive access

Concrete things you can do with federated identity:

– Conditional access policies

Example:

– “If user is in ‘Privileged Admins’, require hardware key (WebAuthn) and compliant device.”

– “Block login from new country unless additional verification passes.”

– Group‑driven authorization

– Map IdP groups to ZTNA app policies.

– Map same groups to cloud IAM roles (AWS IAM, GCP IAM, Azure RBAC).

– Token‑based access to infrastructure

Instead of SSH keys scattered everywhere, use:

– short‑lived SSH certificates tied to IdP identity

– cloud CLI logins via OIDC/SAML (e.g., `aws sso`, `gcloud auth login –enable-gdrive-access`)

Now your cloud resources, ZTNA policies, and any remaining VPN solution all speak the same “identity language”.

—

Non‑standard ideas to level up remote access security

Most advice stops at: *“Use ZTNA, use MFA, integrate IdP.”* Let’s go further and consider a few slightly unconventional moves.

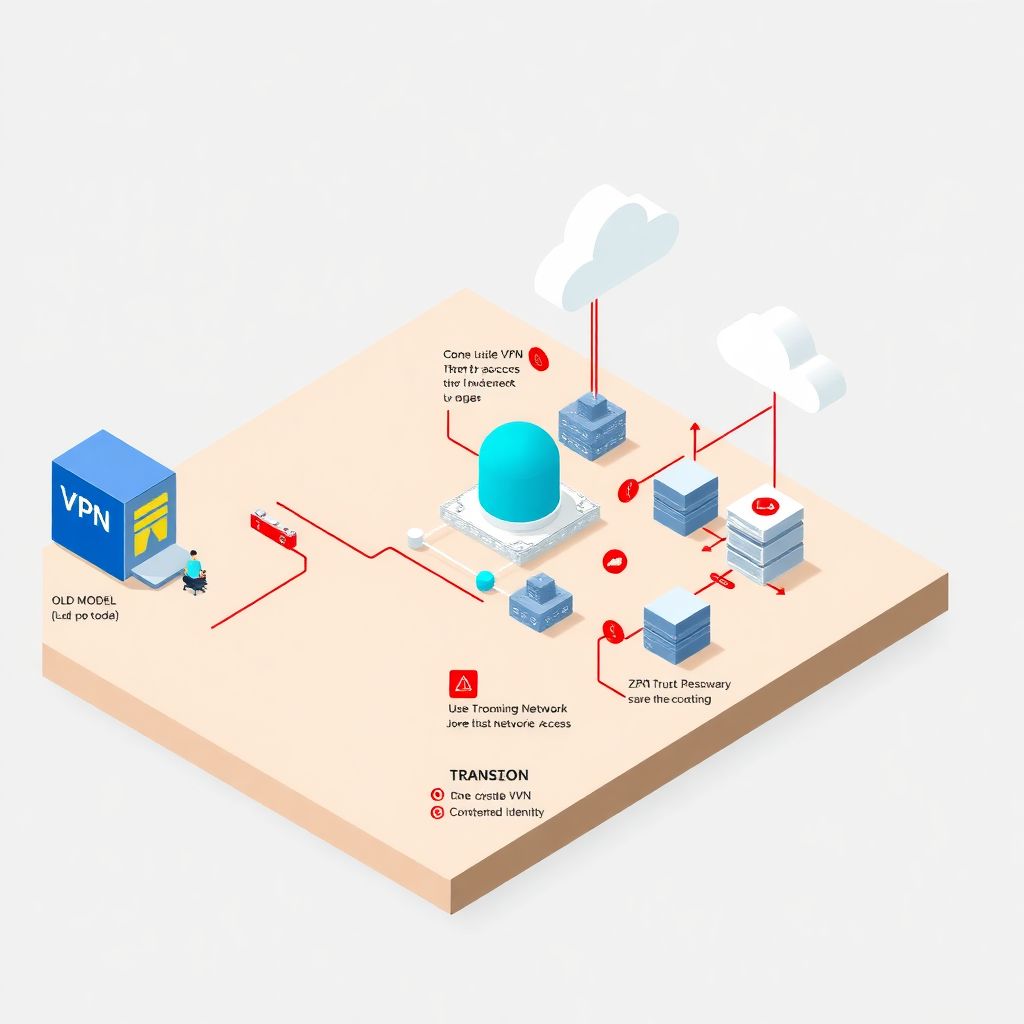

1. “VPN‑only to ZTNA”: make the VPN a dumb pipe

If you can’t get rid of VPN quickly, neuter it:

– Configure VPN so it:

– only reaches the ZTNA connectors or a small set of “jump” endpoints

– does not have direct reach to application subnets

– Force all user traffic to apps through ZTNA even when they’re on VPN

Effect:

– The VPN becomes just an encrypted pipe (e.g., for countries where ZTNA cloud edges are blocked, or for strict ISP environments).

– ZTNA still does the access control and visibility filtering.

This pattern is handy in regulated environments that still “require VPN” on paper, while you quietly apply Zero Trust.

—

2. Freeze static credentials: go 100% ephemeral for admins

For engineers accessing production cloud infrastructure:

– No permanent VPN passwords

– No long‑lived cloud access keys

– No static SSH keys

Instead:

– Authenticate via federated identity with strong MFA

– Obtain short‑lived:

– ZTNA sessions (e.g., 8–12 hours)

– SSH certificates (15–60 minutes)

– cloud IAM tokens (up to 1 hour, renewed via IdP)

If an attacker steals something:

– They get a rapidly expiring token, not a master key

– You have much better logs (each token mapped to a human identity)

This radically reduces blast radius even if there is a laptop compromise.

—

3. Use “internet‑first” design: expose apps safely, not networks

Traditional thinking:

> “If it’s important, keep it off the internet and put it behind VPN.”

Modern alternative:

> “Expose apps to the internet *through* strong identity and ZTNA, but never expose the network.”

Concretely:

– Admin web UIs:

– only reachable via ZTNA; no public DNS, no public IP to the app server

– cloud firewall only allows connections from ZTNA connector IPs

– Developer tools (Git, CI/CD, issue trackers):

– accessible directly via browser + SSO + device checks

– no need to fire up VPN for daily work

This can actually be safer than VPN:

– Nobody can scan your internal IP ranges.

– Every request is authenticated at application layer.

– Misconfigured firewall rule doesn’t instantly expose half your data center.

—

4. Attack‑driven design: build around your worst‑case scenario

Instead of designing around “happy path”, assume:

– a user’s laptop is compromised

– their credentials are phished

– attacker has some time before you notice

Now ask:

– Can the attacker move from cloud dev environment to production?

– Can they reach spare VPN subnets, backup networks, or legacy RDP servers?

– Does ZTNA actually block lateral movement, or just front‑door access?

Non‑standard move:

– Run a red‑team or purple‑team exercise focused only on remote access:

– start from a simulated compromised endpoint

– see which paths exist *after* VPN or ZTNA authentication

– Use the results to harden policies:

– narrower access scopes

– stronger device posture checks

– “just‑in‑time” admin elevation instead of always‑on privileges

This is often more revealing than a generic pentest.

—

Step‑by‑step roadmap: from VPN‑centric to identity‑centric

You don’t need a big‑bang migration. A realistic path:

– Step 1 – Inventory and risk mapping

– List all remote entry points: VPN, RDP gateways, bastions, cloud consoles.

– Identify highest‑impact targets: admin portals, production databases, CI/CD, backup systems.

– Step 2 – Centralize identity

– Choose / consolidate your IdP.

– Turn on MFA (preferably app‑based or hardware keys, not SMS).

– Integrate critical SaaS apps and cloud providers with SAML/OIDC.

– Step 3 – Introduce ZTNA for new and critical apps

– Start with admin consoles and production apps.

– Wire them behind ZTNA, tied to IdP groups and conditional access.

– For developers/admins, pilot device posture checks.

– Step 4 – Tame the VPN

– Segment: separate networks for dev, prod, corporate IT.

– Restrict what VPN users can see; remove broad “any/any” rules.

– Gradually direct more traffic through ZTNA instead of raw VPN.

– Step 5 – Go ephemeral for sensitive access

– Introduce short‑lived tokens and certificates for admin work.

– Remove shared admin accounts and static keys.

– Step 6 – Monitor, simulate attacks, adjust

– Centralize logs from IdP, ZTNA, VPN, and cloud.

– Regularly test “compromised user” scenarios and tighten gaps.

This is how you turn “segurança acesso remoto infraestrutura cloud” from a collection of products into a coherent, identity‑centric architecture.

—

Closing thoughts

Remote access security is no longer about “do I have a VPN or not?”.

It’s about:

– making networks boring and invisible

– making identity and device posture the first line of defense

– using ZTNA to expose applications, not subnets

– and embracing short‑lived, auditable access for everything that matters

If you treat VPN, ZTNA, and identidade federada na nuvem para acesso remoto as parts of one system—not competing silos—you can get to a point where:

– a stolen password is annoying, not catastrophic

– a compromised laptop has limited reach

– and granting or revoking access is a 5‑minute task, not a 5‑day project.

That’s the real upgrade: not just new tools, but a different mental model for serviços de segurança em acesso remoto cloud.