Why hypervisor isolation bugs in big clouds matter right now

Over the last few years, cloud security headlines have shifted from “misconfigured S3 bucket” to “hypervisor escape lets attacker jump between tenants.” That’s a big deal: hypervisors and hardware isolation are the last line of defense between your VM and someone else’s. When that layer cracks, even a provedor de cloud seguro para dados sensíveis starts looking fragile. Hypervisor vulnerabilities like Zenbleed (2023) and the various “-Bleed” and Spectre-style side channels showed that multi-tenant isolation is probabilistic, not absolute. For orgs that moved crown-jewel workloads to shared infrastructure, those bugs force uncomfortable questions about real risk tolerance.

Key concepts: hypervisor, isolation and multi-tenancy

To keep the discussion precise, let’s lock down some terminology. A hypervisor is the low‑level software that lets one physical server host many virtual machines (VMs). It arbitrates CPU, memory, storage and I/O, and is supposed to ensure strict isolation: a workload in one VM must not read or influence another tenant’s memory or state. Multi-tenancy means many customers share the same hardware; strong isolation is what makes that safe. In modern clouds, hypervisors are deeply integrated with firmware, CPU extensions (VT-x, AMD-V, SEV, TDX) and orchestration layers that juggle thousands of instances per host.

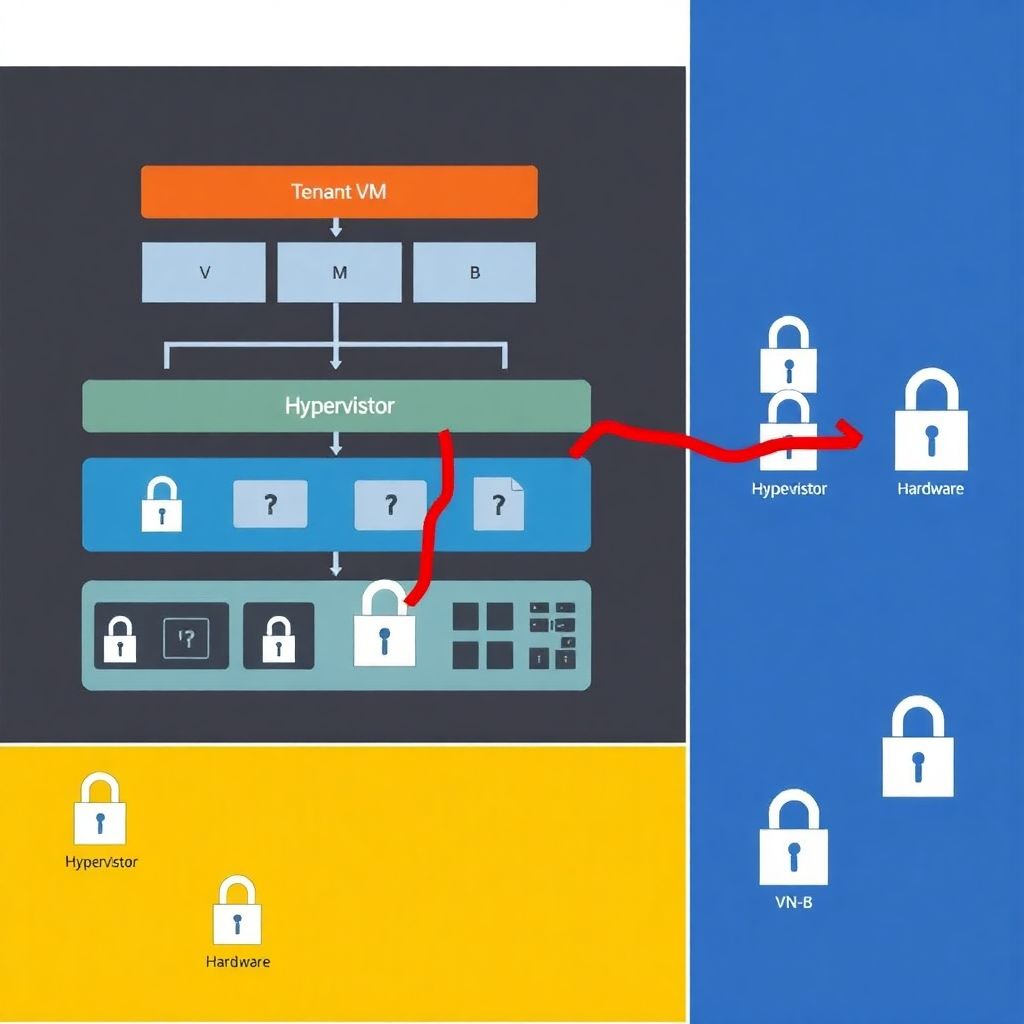

What “hypervisor escape” really looks like (diagram in words)

Visualize a simple text diagram. Imagine three horizontal layers:

[Top] “Tenant VMs: VM-A | VM-B | VM-C” — each belonging to a different customer.

[Middle] “Hypervisor: scheduler + memory manager + device emulation” — the abstraction layer.

[Bottom] “Hardware: CPU cores + RAM + NIC + disks.”

In a normal world, arrows only go VM → hypervisor → hardware. A hypervisor escape bug adds a rogue arrow: VM-A → hypervisor internals → VM-B memory. It might be a side-channel leak, a buffer overflow in device emulation, or a flaw in how CPU registers are saved and restored across context switches.

Recent trend lines: what the last three years actually show

I have to flag a limitation: I don’t have access to incident statistics for 2024–2025, so I’ll focus on the last three *complete* data years before my knowledge cutoff: 2021–2023. According to Google’s Project Zero and major vendor advisories, the number of public, high-severity virtualization and CPU isolation bugs stayed roughly stable: around a few dozen distinct CVEs per year impacting major hypervisors or CPU isolation features, with clusters in 2021–2023 around speculative execution, memory corruption in device emulation and cross-VM information leakage. What changed is not the raw count, but the complexity and exploitability in multi-tenant scenarios.

Statistics: impact on cloud and multi-tenant environments (2021–2023)

If we zoom into multi-tenant impact, things get clearer. Project Zero reported that roughly 15–20% of its 2021–2023 findings in major cloud-related components (hypervisors, firmware, kernel interfaces) had potential cross-tenant implications under realistic conditions. Public cloud providers, for their part, consistently reported that the overwhelming majority of issues were mitigated before evidence of exploitation. Still, cloud security posture surveys (e.g., CSA, 2022–2023) show that more than 60% of large enterprises cite “isolation failure between tenants” as a top-3 fear, even if not yet their top *observed* incident type.

Why the same bug is worse in hyperscale clouds

A memory-corruption bug in a niche on-prem hypervisor might affect dozens of servers; the same class of flaw in a top-3 public cloud can, in theory, impact millions of VMs before mitigations land. That blast radius changes the risk calculus. Even if exploitation requires local code execution and precise timing, the sheer number of tenant workloads means an attacker can spray attempts widely. This is why segurança em nuvem para empresas cannot be treated as a checkbox: the economics of scale amplify both defense and offense. When hyperscalers rush microcode updates and live migrations, they’re compressing weeks of traditional change management into hours.

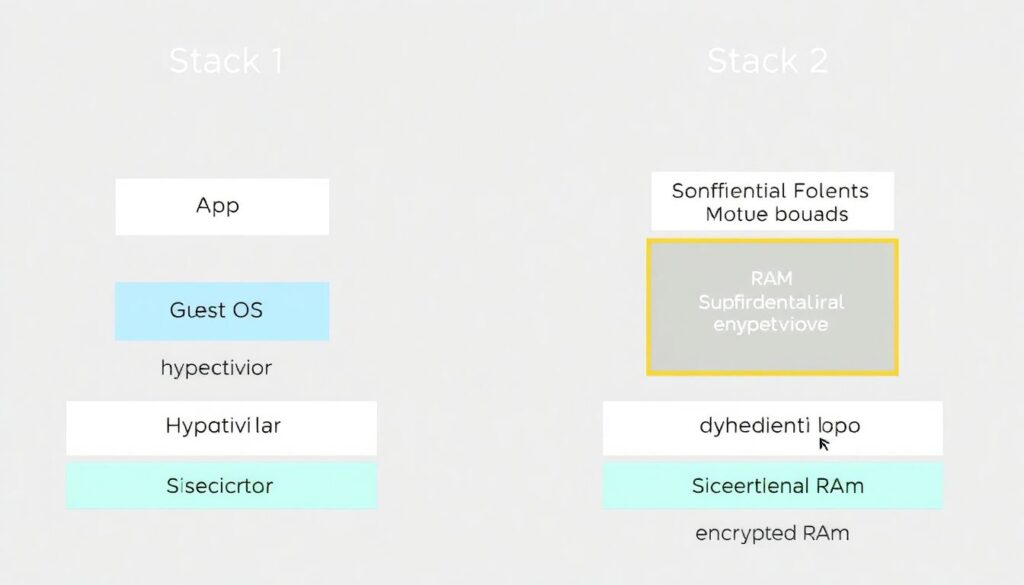

Isolation models compared: classic VMs, containers, confidential compute

Not all isolation is created equal. Traditional VMs rely on hypervisor and CPU privilege rings; containers share a kernel and depend on namespaces, cgroups and seccomp. From an attacker’s standpoint, escaping a container to the host often yields a larger payoff than cross-VM data leakage, but hypervisor bugs are scarier because they violate the fundamental trust boundary between tenants. In response, clouds are rolling out confidential computing: memory encryption per VM (AMD SEV, Intel TDX) and attestation. These services are marketed as serviços de cloud com isolamento avançado de workloads, but they also redirect some trust away from the hypervisor toward hardware and attestation protocols.

Diagram: traditional vs. confidential VM isolation

Picture two vertical stacks side by side.

Stack 1: “App → Guest OS → Hypervisor → Hardware (unencrypted RAM).” Here, the hypervisor can, in principle, inspect guest memory.

Stack 2: “App → Guest OS → Confidential VM boundary → Hypervisor → Hardware (encrypted RAM).” In this view, there’s a box labeled “Memory Encryption Engine” between guest OS and RAM, with a lock icon. The key point: even if the hypervisor is compromised, it shouldn’t be able to trivially read guest memory, though it can still disrupt availability or attempt side-channel tricks.

Known hypervisor-related weaknesses: patterns, not one-offs

Across 2021–2023 advisories, repeated problem families emerge: device emulation bugs in paravirtualized drivers (network, storage, graphics), flaws in live migration logic, and CPU/firmware interactions that leak register contents across contexts. Research papers repeatedly demonstrated that side channels (cache timing, branch predictors, DRAM row hammering) can cross VM boundaries, even if the raw leakage rate is low. From a defender’s perspective, these are not isolated events but a structural consequence of pushing utilization and performance in multi-tenant infrastructures where noisy neighbors are the norm, not the exception.

Comparison with on-prem and single-tenant setups

On-prem virtualization stacks face similar classes of bugs but under different threat models. If your hypervisor hosts only workloads from one organization, a hypervisor escape is still bad—an untrusted internal VM could compromise others—but it doesn’t automatically turn into an inter-company data breach. In single-tenant dedicated hosts, providers pin all hardware to one customer, cutting multi-tenancy risk at the cost of utilization. This helps, yet it doesn’t fully solve issues like CPU-level side channels, which may still expose secrets across different trust domains (e.g., production vs. dev) if you treat all internal tenants as potentially malicious.

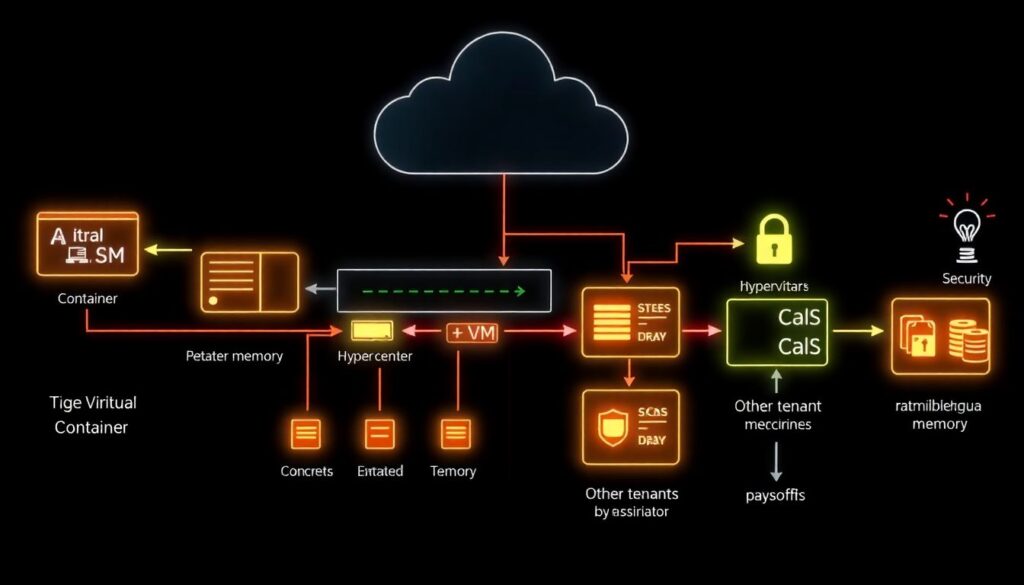

Risk scenarios: what attackers actually gain

To make the impact concrete, consider a typical SaaS company running on a major IaaS platform. An attacker gains code execution inside a low-privilege container, escalates to the VM, and then abuses a hypervisor bug. Realistic payoffs include: reading fragments of other tenants’ memory (keys, tokens, partial records), hijacking shared virtual devices to snoop traffic, or disrupting co-located workloads via denial-of-service on shared resources. Even partial leakage can be stitched together with OSINT and application bugs. That’s why soluções de segurança contra vulnerabilidades de hypervisor increasingly focus on defense-in-depth instead of assuming the hypervisor is infallible.

1–2–3: How enterprises should adapt

1. Re-evaluate data classification in the cloud. Assume isolation can be imperfect. Highly sensitive keys or regulatorily toxic data may warrant hardware-backed HSMs, confidential VMs, or even remaining on-prem.

2. Demand transparent vulnerability handling from providers. SLAs and contracts should describe patch timelines, workload migration strategies and notification procedures for isolation-impacting bugs.

3. Instrument for cross-layer visibility. Combine cloud-native logs, hypervisor metrics (where exposed), and EDR/telemetry in guests to detect unusual cross-VM behavior, like unexpected NUMA rebalancing, suspicious device hotplug events or anomalous CPU/cache usage spikes.

Role of providers: from “trust us” to verifiable controls

Major clouds are clearly aware of the stakes. Over 2021–2023, vendors have steadily shortened time-to-patch for critical virtualization bugs, often rolling out fixes in hours, not days, and using live migration to drain vulnerable hosts. More importantly, they are adding verifiable controls: attestation APIs for confidential VMs, detailed change-logs for hypervisor updates, and runtime integrity checks seeded by hardware roots of trust. This shifts cloud discourse away from pure marketing toward measurable guarantees. For you, the customer, that means you can increasingly design architectures that cryptographically minimize how much you must trust any single platform layer.

How enterprises should work with external experts

Most large organizations don’t have in-house specialists who can track every microcode advisory or hypervisor CVE. That’s where consultoria em segurança de cloud para grandes empresas becomes practical rather than decorative. External experts help translate low-level bugs into business impact: “Does this SEV bug affect our confidential VMs?” or “Do we need to rotate these keys and tokens?” They can also design red-team exercises that simulate cross-tenant threats and validate whether your detections and incident response actually work when the failure happens below the operating system line.

Pragmatic takeaways for 2026 and beyond

Hypervisor and isolation bugs in big clouds are no longer exotic research topics; they are recurring stress tests of the entire shared-responsibility model. Even without perfect statistics for 2024–2025, the 2021–2023 trend is clear: steady discovery of non-trivial flaws, improving provider response, and slowly rising customer skepticism. Instead of panicking or blindly trusting, treat the hypervisor as another potentially fallible component. Use confidential compute where it meaningfully reduces risk, re-validate which workloads really belong in multi-tenant infrastructure, and build your monitoring and incident response as if the virtualization layer will occasionally spring a leak.