Why hardening Kubernetes hurts (until it doesn’t)

If you’ve ever tried to “secure the cluster later”, you already know how this story goes: messy RBAC, random Helm charts from the internet, half‑configured network policies, and a vague hope that the cloud provider’s defaults are “good enough”.

They aren’t.

Hardening Kubernetes is painful mainly because it cuts across everything: cluster bootstrap, network, CI/CD, workloads, and even how teams collaborate. But with a practical guide and real examples, you can move from “maybe it’s fine” to predictable, auditable segurança kubernetes em produção.

Let’s walk through it step by step: from cluster to workload, with real‑world war stories and some non‑obvious tricks that don’t usually make it into glossy vendor whitepapers.

—

Start at the cluster: if the base is weak, everything is weak

Control plane: don’t trust the managed defaults blindly

Managed Kubernetes (EKS, GKE, AKS, etc.) creates the illusion that the control plane is “handled”. In reality, you still make decisions that can weaken or strengthen it.

A short checklist that saves a lot of pain:

– Ensure API server is *private* or at least IP‑restricted

– Enforce strong auth: OIDC + SSO, no long‑lived static tokens

– Disable anonymous auth and legacy ABAC if available

– Turn on audit logging and actually ship logs somewhere

Real case – “Our cluster got noisy, not hacked”

One team I worked with had exposed the Kubernetes API to the internet with only a simple IP whitelist. Someone misconfigured a jump box, opening that IP to the world. Botnets started hammering `/api` and `/apis` endpoints.

No data exfiltration happened, but:

– API server CPU shot up

– Cluster started throttling normal traffic

– Incident lasted hours because nobody was monitoring API audit logs

The fix wasn’t just “close the port”. We:

– Switched API endpoint to private + VPN

– Introduced short‑lived kubeconfigs via SSO

– Alerted on abnormal API request rates

Hardening the control plane is not glamorous, but it’s one of the hardening kubernetes melhores práticas that repeatedly proves its value in production incidents.

—

etcd: your entire cluster’s memory, in plain text

etcd stores secrets, config, and state. Treat it as a database full of crown jewels.

For self‑managed clusters:

– Enable encryption at rest for etcd data directory

– Use TLS for all etcd client/server traffic

– Separate etcd nodes (or at least disks) from general workloads

A non‑obvious trick:

If you’re migrating from an older cluster that didn’t encrypt etcd, plan a rolling re‑encryption. People often enable encryption in config and assume everything is protected, but old data remains unencrypted until rewritten.

—

Networking: from flat cluster to segmented blast radius

Network policies: start with “deny all” (carefully)

Most clusters start flat: every pod can talk to every other pod. That’s great for demos and terrible for real environments.

The classic pattern:

1. Introduce a “default deny” NetworkPolicy per namespace

2. Add “allow from ingress controller” and “allow to database” rules

3. Keep pod labels clean and meaningful – they are your future firewall tags

Real case – Lateral movement through a debugging pod

A team left a “debug” namespace wide open. A compromised application pod in another namespace used stolen service account credentials to schedule a pod in that debug namespace with broad network access, then laterally moved to a stateful service.

The attack path wasn’t sophisticated. What made it possible:

– No default deny policies

– Service accounts with overly permissive RBAC

– No egress restrictions

Fixing it:

– Default deny on all namespaces

– Separate “ops-debug” namespace with strict RBAC and manual approvals

– Restrict pod creation rights to a small group

Alternative approach:

If you’re overwhelmed by NetworkPolicy complexity, start with “high‑risk namespaces first”: production + shared infrastructure (ingress, monitoring, CI/CD agents). That gives you 80% of the benefit without blocking development namespaces too early.

—

Ingress and egress: TLS, WAF, and the “everything talks to the internet” problem

Ingress is usually better understood: TLS termination, WAF, sane headers.

The less obvious side is egress. Most clusters silently allow every pod to talk to the entire internet. That’s a dream for data exfiltration.

Practical measures:

– Use egress policies (Kubernetes or CNI‑specific) to restrict outbound traffic

– Route all egress through a NAT or proxy with logging

– Maintain an “egress allowlist” per app or namespace

A professional‑grade “hack”:

– Treat egress like S3 buckets: public by explicit exception only

– Build Terraform modules or Helm charts that create the minimal egress rules per service

– Expose these options to developers as code, not tickets

—

Identity and RBAC: your real perimeter

Service accounts: stop using `default`

The `default` service account is the Kubernetes equivalent of “admin/admin” passwords. It seems harmless, then becomes a liability.

Basic but powerful rules:

– Never mount tokens to pods that don’t need Kubernetes API access

– Create a dedicated service account per application or per role

– Attach fine‑grained Role/RoleBinding to each service account

Real case – Token exfiltration through logs

A logging sidecar was configured to dump environment variables on startup for troubleshooting. The pod used the namespace’s default service account. When the node crashed, logs were uploaded to a central system where the token remained visible.

Later, during an internal red‑team exercise, the token was used to:

– Read secrets in the namespace

– List pods across multiple namespaces

– Enumerate internal services and endpoints

All from a single exposed token.

The remediation included:

– Separate service accounts and RBAC per deployment

– TokenProjection with shorter‑lived tokens

– Disabling token mounting for services that never talk to the API

—

Human access: kubeconfigs, SSO and just‑enough rights

For humans, consultoria segurança kubernetes often recommends a very predictable workflow:

– Use one identity provider (IdP) for cluster access (OIDC)

– Assign roles by group (Dev, Ops, Security, ReadOnly)

– Remove static, long‑lived admin kubeconfigs

A less obvious step:

Create separate “break‑glass” admin access with:

– Stronger MFA policies

– Clear logging and approval trail

– Rotated credentials and strict use policy

That way, day‑to‑day work happens with least privilege, but teams can still recover from ugly incidents without playing games with credentials at 3 a.m.

—

Workload security: images, pods, and runtime habits

Images: slim, signed, and scanned (in CI, not just in prod)

Image security is where theory and reality diverge. It’s easy to say “only use trusted images”; it’s harder when deadlines loom.

Start with these guardrails:

– Base images: `distroless` or minimal OS when possible

– Fully pinned image versions (`myapp:1.2.3`, not `latest`)

– Vulnerability scans on each build, with severity thresholds

Bring in ferramentas de segurança para kubernetes that plug into your CI/CD:

– Image scanning (e.g., Trivy, Grype, etc.)

– Policy‑as‑code (e.g., OPA/Gatekeeper, Kyverno) to reject non‑compliant manifests

– Container signing (e.g., cosign) with admission control enforcing signatures

Real case – “We scanned prod weekly and still got caught”

One enterprise only scanned running images weekly. A critical RCE appeared in a popular base image; before the next scheduled scan, the vulnerable image was deployed in response to a hotfix request.

Switching to:

– Scan on build

– Sign on build

– Admit only signed and compliant images

…reduced exposure windows from days to minutes.

—

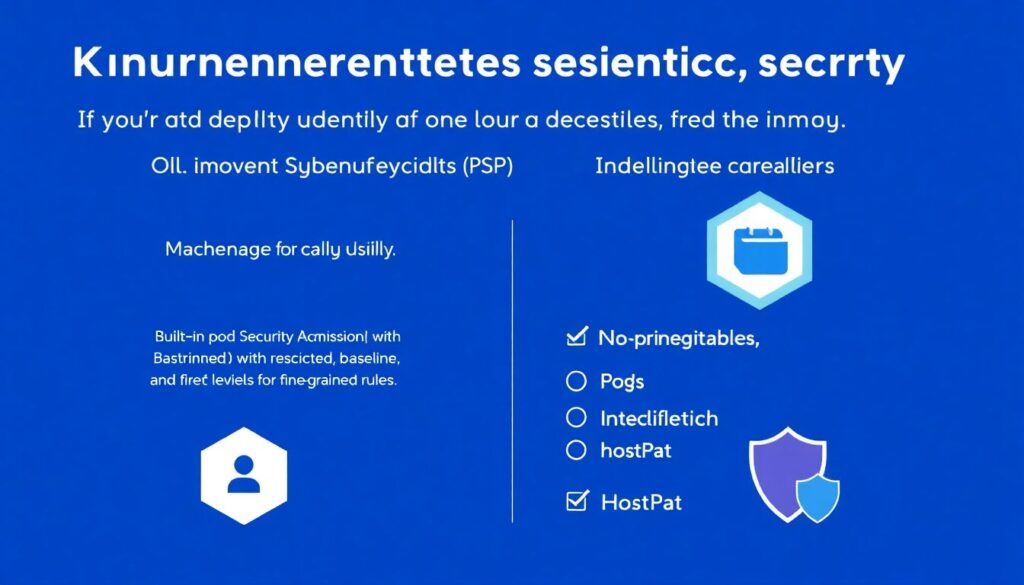

Pod security: from PSP to Pod Security Standards and beyond

If you’re still depending on PodSecurityPolicies (PSP), it’s time to move on. Modern clusters use:

– Built‑in Pod Security Admission (restricted/baseline/privileged levels)

– Additional policy engines for fine‑grained rules

Non‑negotiables for production pods:

– No privileged containers

– No hostPath mounts unless strictly necessary

– Read‑only root file system when possible

– Drop all capabilities, add only specific ones back (e.g. `NET_BIND_SERVICE`)

Pro tip for professionals:

Start in “audit” mode. Configure Pod Security to log violations before enforcing. Gather at least a week of data, fix the obvious offenders, then progressively turn on “enforce” per namespace. This avoids the classic security vs. devs war.

—

Secrets: environment variables are not a vault

Kubernetes Secrets are better than ConfigMaps but are still just base64‑encoded data stored in etcd.

Practical layering:

– Encrypt secrets at rest in etcd (cluster setting)

– Integrate with external secrets managers (Vault, AWS Secrets Manager, etc.)

– Make secrets short‑lived when talking to external systems (DB tokens, API keys)

A non‑obvious risk:

Environment variable secrets are easily exposed through:

– Crash logs

– `kubectl describe pod` output

– Misconfigured debug endpoints that dump env

Whenever possible:

– Mount secrets as files, not env vars

– Use secret‑aware SDKs that reload credentials when rotated

– Limit who can run `kubectl exec` or `kubectl describe` in production

—

Observability, threat detection and compliance

Logs, metrics and traces with security in mind

Monitoring isn’t just about “is it up?”; it’s also about “is someone doing something weird?”.

For proper monitoramento e compliance kubernetes:

– Send API audit logs to a central logging system

– Tag logs by namespace, team, and environment

– Track key security metrics: denied requests, failed logins, unusual pod restarts

Security‑driven alerts you actually want:

– Sudden spike in API server 401/403

– Unexpected creation of privileged pods

– New use of hostPath or hostNetwork in prod

– Changes to ClusterRoleBindings outside of maintenance windows

Real case – Detection through weird DNS

A team noticed a spike in DNS queries from a single pod to random domains. Resource usage looked fine; application metrics were normal.

On deeper inspection:

– A malicious image had been introduced in a less‑controlled dev namespace

– Attackers used it to run a crypto‑miner with DNS‑based C2

Because DNS metrics were integrated into cluster monitoring, the anomaly was caught in under an hour, before serious cost or data issues.

—

Policies and audits: codifying “how we do things”

Policies are where hardening kubernetes melhores práticas become enforceable rules instead of tribal knowledge. This is usually where security teams or external consultoria segurança kubernetes bring a lot of value.

Key techniques:

– Use policy‑as‑code (OPA/Gatekeeper, Kyverno) to enforce:

– No `latest` images

– No privileged pods or hostPath in prod

– Mandatory labels/annotations for ownership and data sensitivity

– Run periodic cluster audits with tools like:

– CIS benchmark scanners

– RBAC analyzers

– Image/registry audits

This isn’t just about being “secure”; it’s also how you show auditors and management that your Kubernetes security posture is measurable and improving over time.

—

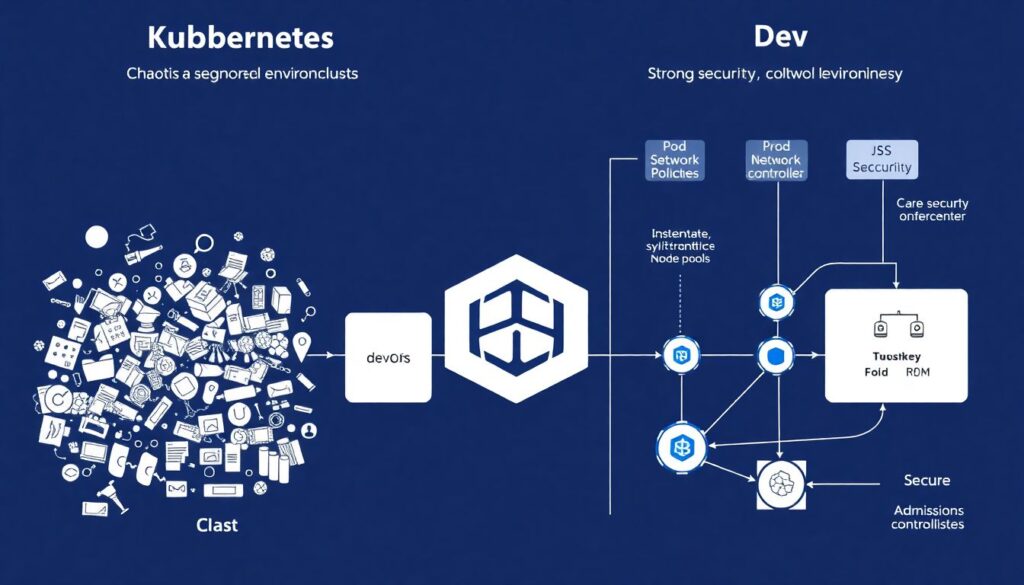

Non‑obvious solutions and alternative paths

When you can’t fix everything at once: segmentation and “guardrail first” strategy

Most teams inherit a messy cluster. You won’t get from chaos to perfect in one sprint.

A practical phased approach:

– Segment environments: prod, staging, dev in separate clusters or at least separate node pools

– Focus all strong controls on prod first (Pod Security, NetworkPolicies, admission controls)

– In dev, focus on visibility: strong logging, easy detection, and fast feedback to developers

Alternative method:

Instead of fighting every insecure pattern, define a golden path:

– A “secure app template” (Helm chart or Kustomize base) with:

– Non‑root user

– Resource limits

– Correct probes

– SecurityContext baked in

– CI templates with scanning, signing, and deployment checks

Developers copy the template and automatically inherit 80% of your security model. You then use policies to block deviations from the template in prod.

—

Pro tips and “lifehacks” from production experience

A few practical tricks that help teams move faster without compromising:

– Namespace as a contract

Treat each namespace like a “tenant” with:

– Clear owners (labels/annotations)

– Explicit resource and security policies

– Specific RBAC groups

– Security dashboards by team, not by cluster

Developers care about *their* services. Build dashboards and reports by namespace or team, surfacing:

– Vulnerable images

– Policy violations

– Recent incidents

– Canary enforcement

When introducing a new policy (e.g., no privileged pods), start by enforcing it only in a small, representative subset of namespaces. Fix any breakage there, then roll out cluster‑wide.

– “Security Champion” in each squad

Identify one engineer per team who understands Kubernetes security enough to translate global policies into local practice. This massively reduces friction and speeds up adoption of new controls.

—

Pulling it all together: from theory to day‑to‑day practice

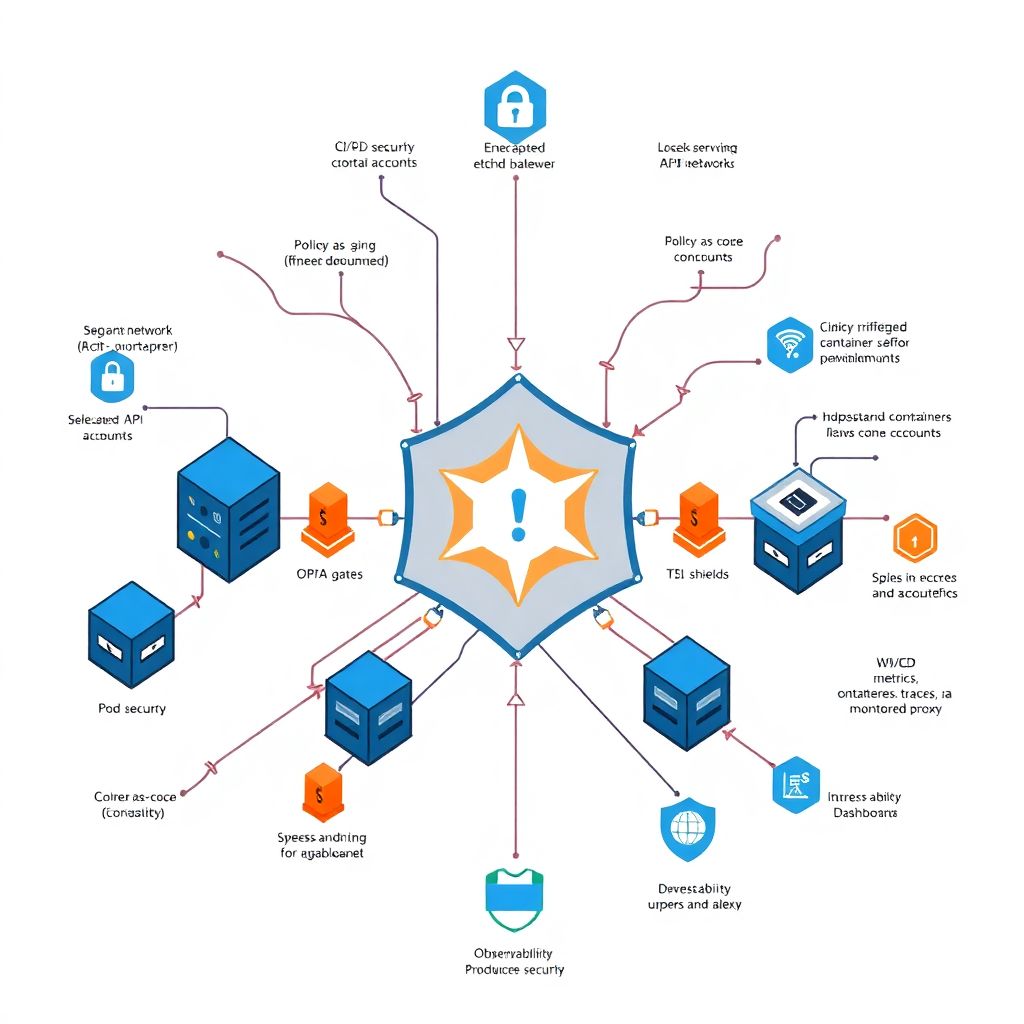

Hardening Kubernetes isn’t a one‑off project; it’s a continuous process where you:

– Secure the cluster base (API, etcd, networking, identity)

– Lock down workloads (images, pods, secrets)

– Invest in good visibility and policy enforcement

– Keep humans and processes aligned around how things *should* be done

The difference between an over‑secured but unusable platform and healthy segurança kubernetes em produção is how well security integrates with developer workflows. If policies live only in PowerPoint and not in CI/CD and manifests, they’ll be ignored.

Treat every change as code, provide secure templates, and let developers see the impact of their choices through clear monitoring and feedback. With that, hardening stops being a burden and becomes just “how we run Kubernetes here” – from cluster to workload, reliably, in production.