Sensitive data in the cloud is a bit like putting your company’s safes in someone else’s building: convenient, scalable, but suddenly you care a lot more about doors, locks and who has which keys. When we talk about proteção de dados sensíveis em cloud today, we’re really talking about three pillars that need to work together: encryption, tokenization, and key management (KMS/HSM). Mess up any one of them, and the whole setup starts to wobble.

Below is a practical, problem‑oriented walkthrough, with real cases, non‑obvious tricks, and some war‑stories from the field.

—

Why “just encrypt everything” is not a strategy

Most teams start with a naive plan: “we’ll enable encryption at rest in our cloud provider and call it a day.” That’s how you get a false sense of segurança de dados na nuvem com criptografia without actually solving the full problem.

The three big problems everyone underestimates

1. Where data actually lives

Sensitive data is rarely only in your main database. It leaks into:

– logs

– analytics and BI systems

– caches and message queues

– incident screenshots and debug dumps

If you don’t account for all of these, you have shadow copies of production data floating around unprotected.

2. Who can see what

If every admin, developer and support engineer can decrypt everything “just in case”, you haven’t gained much. Access control and key scoping matter as much as the cipher you choose.

3. Key lifecycle

Keys live, rotate, expire, and eventually must be destroyed. If that lifecycle isn’t designed and automated, you’ll either stall deployments or end up disabling security “temporarily” — which then becomes permanent.

—

Encryption in cloud: the necessary but insufficient layer

Basic vs. real‑world encryption

Cloud providers make it easy to turn on “encryption at rest” for storage, databases and volumes. Do it; there’s no excuse not to. But understand its limits:

– It mainly protects against physical theft of media or a compromised storage layer.

– It does not protect against:

– an attacker using valid credentials

– an over‑privileged admin

– a compromised application server reading plaintext

In other words, the built‑in feature is the foundation, not the full house.

Case: SaaS startup with “secure” but leaky analytics

A B2B SaaS startup migrated to a managed cloud database, flipped on encryption at rest, and advertised “bank‑grade security”. Then they plugged in a third‑party analytics tool by exporting nightly CSVs of customer activity to object storage.

Two issues appeared:

– The analytics vendor’s service account had wide read access to the bucket.

– Raw exports included names, emails and partial card data.

The vendor was breached. The storage buckets were technically encrypted, but the attacker got in through the vendor’s credentials and downloaded the files in plaintext.

What they did after the fact:

– Switched to application‑level encryption for payment‑related attributes before data even hit the database or exports.

– Gave the analytics vendor access only to pre‑aggregated, anonymized datasets.

– Enforced KMS‑backed keys tied to an IAM role with strong conditions (IP restrictions, MFA for role assumption in sensitive paths).

Overnight, they moved from “encryption as a checkbox” to a more realistic threat model where an external vendor breach doesn’t automatically expose raw customer data.

—

Tokenization: when encryption is not enough

Encryption is reversible by design. If you have the key, you get the plaintext. Tokenization goes further: you replace sensitive values with tokens that cannot be mathematically reversed without a dedicated mapping service.

What tokenization really solves

– Minimizes where sensitive data is stored.

– Reduces the blast radius if a database or log store is compromised.

– Helps a lot with proteção de dados confidenciais em nuvem para compliance LGPD by reducing what is considered “personal data” in many systems.

Instead of persisting a CPF, PAN, or medical identifier everywhere, you store and pass around tokens. The actual value lives in a tightly controlled token vault.

Case: Payment processor cutting 80% of its PCI scope

A mid‑size payment provider ran dozens of microservices, and card numbers flowed almost everywhere: risk engine, notifications, billing, reporting. PCI DSS scope (and cost) was huge.

They introduced soluções de tokenização de dados sensíveis em cloud with a dedicated tokenization service:

– Card data only entered through a small set of front‑door services.

– Those services called a tokenization API that returned:

– A random token for storage.

– A truncated, formatted “display version” of the card for UI purposes.

– Downstream services never saw the real PAN, just tokens.

Results:

– Only 3–4 core services remained in PCI scope; dozens were scoped out.

– Compromise of a single service or database no longer yielded real card data.

– Incident response became more surgical, because they knew exactly which components ever touched real PANs.

Tokenization isn’t only for payments. It works similarly for national IDs, email addresses, phone numbers, even internal employee IDs.

—

Key management: KMS, HSM and where people get burned

Encryption and tokenization are only as strong as your key discipline. That’s where serviço de gestão de chaves KMS HSM para empresas comes in.

KMS vs HSM in practice

– KMS (Key Management Service): managed service that handles:

– key storage

– rotation

– access control and audit logging

Often integrated directly into cloud services (databases, storage, queues).

– HSM (Hardware Security Module): physical or virtual hardware boundary with strict cryptographic guarantees, often required by regulators or high‑assurance environments (financial, defense).

A practical mental model:

Use KMS as the control plane for keys. Use HSM‑backed keys when you need provable hardware isolation or compliance with specific standards (e.g., FIPS 140‑2 Level 3).

Real‑world failure: the forgotten test KMS key

A large enterprise had an elaborate KMS setup in production: customer master keys per environment, automatic rotation, strict IAM rules. Their staging environment, however, was “simplified for development”.

A contractor accidentally:

– Used a staging KMS key for a production migration test.

– Exfiltrated a backup encrypted with that staging key.

– After the project ended, the staging project (and with it, the key) was deleted.

Months later, they needed to restore historical data for an audit. The backup was intact. The key was gone. Data was effectively shredded.

This wasn’t a security breach; it was an availability disaster caused by sloppy key lifecycle management.

What they changed:

– Treated all keys as production assets, even in test and staging.

– Centralized KMS administration, with clear ownership and documented rotation/destroy policies.

– Implemented a “key usage catalog” mapping each key ID to:

– datasets

– applications

– retention policies

—

Non‑obvious design decisions that change everything

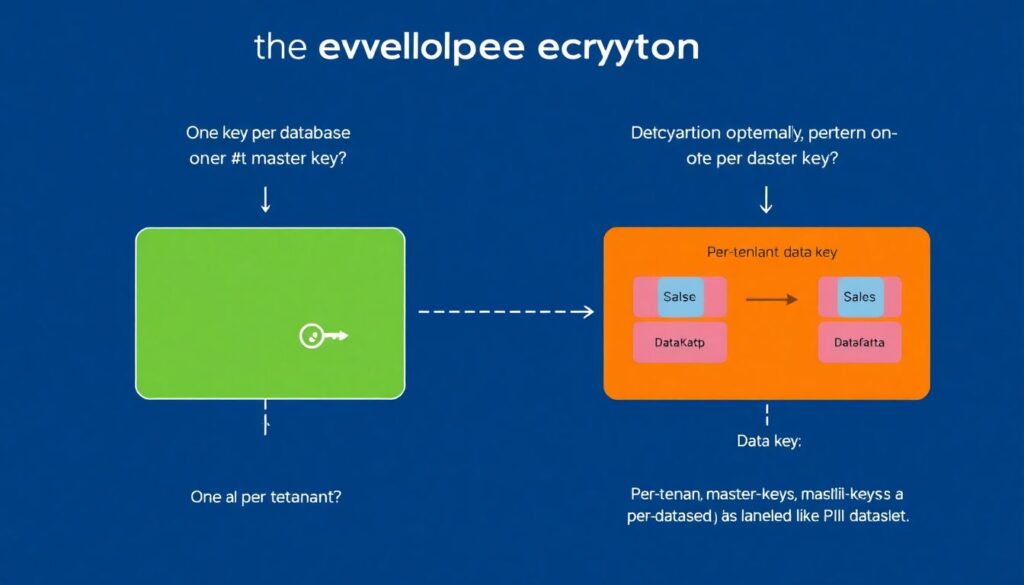

Envelope encryption the right way

Envelope encryption (data keys encrypted by master keys) is standard. The non‑obvious part is granularity:

– One key per database?

– One per tenant?

– One per column or data type?

A common, pragmatic pattern:

– Per‑tenant master key for multi‑tenant SaaS.

– Per‑dataset data key (e.g., for “PII profile data”, “payment data”, “health data”) under each tenant’s master.

Benefits:

– You can destroy one tenant’s master key to effectively “forget” them.

– Compromise of a single data key doesn’t expose every type of data.

– Rotation can be staggered by dataset, reducing performance impact.

Side‑channel: protecting data in logs and traces

Most breaches of “encrypted” platforms happen via logs:

– Structured logs with full request/response bodies.

– Traces containing user IDs, email, and even tokens.

Non‑obvious but effective controls:

– Schema‑driven redaction in your logging pipeline. Mark fields as `sensitive: true` in your schemas and have the logger automatically mask or drop them.

– Tokenization before logging: never log raw identifiers; log tokens or salted hashes instead.

– Sampling‑aware logging: production logs should never capture 100% of payload details; that’s what staging is for.

—

Alternative methods beyond classic encryption and tokenization

Sometimes you need to go beyond the two usual suspects.

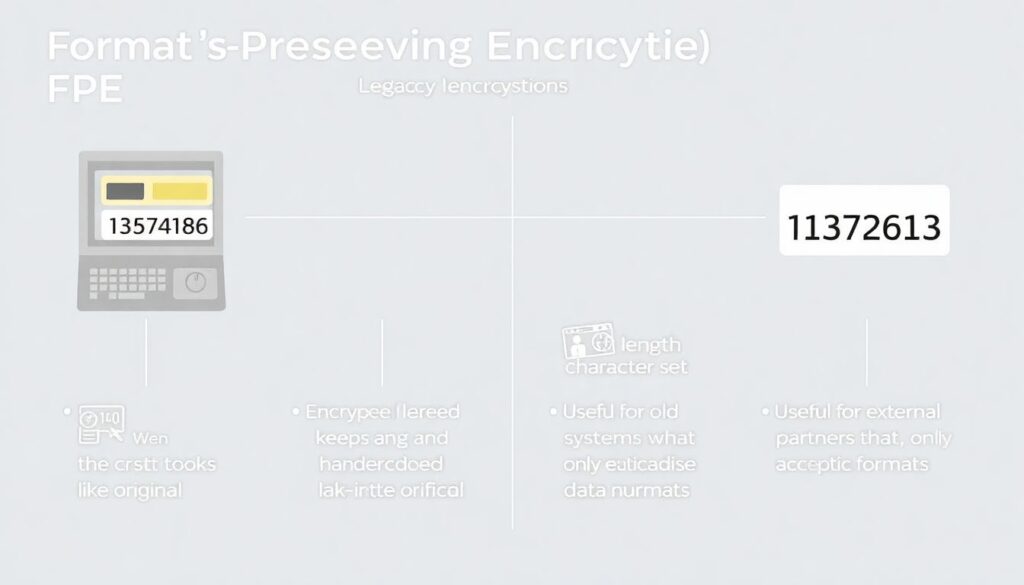

Format‑preserving encryption (FPE)

When legacy systems or field formats can’t change, FPE is useful:

– Keeps the length and character set (e.g., 16‑digit number).

– The stored value “looks like” the original but is encrypted.

Useful for:

– Old systems with hardcoded field lengths.

– External partners that only accept certain data formats.

Caveat: FPE implementations are tricky; use well‑reviewed libraries or vendor solutions, not home‑grown crypto.

Data minimization and synthetic data

One of the strongest protections is not storing the data at all:

– Replace rarely used sensitive datasets with synthetic data in lower environments.

– For analytics, aggregate and anonymize at ingestion instead of copying raw data everywhere.

This drastically shrinks where your plataformas de criptografia e tokenização para cloud corporativa even need to operate.

—

Cloud‑specific case: multi‑cloud identity provider with PII sprawl

An identity provider running across two major clouds discovered that user PII existed in:

– primary relational databases

– search indices

– queuing systems

– ad‑hoc admin exports in object storage

– third‑party monitoring snapshots

They had decent encryption in each platform, but no coherent view.

What they did:

1. Centralized key policy:

– Defined a single, cross‑cloud KMS/HSM policy framework.

– Mapped PII classes (name, login, recovery email, phone, device IDs) to specific key groups.

2. Application‑level controls:

– Introduced a tokenization microservice for high‑risk data (phones, alt‑emails, recovery questions).

– UI and APIs only handled tokens for certain flows.

3. Data discovery & classification:

– Ran continuous scans using DLP‑like rules to find PII in logs, storage, and data lakes.

– Any new system that needed PII had to register in a catalog with a defined protection pattern.

4. Geo‑aware keys:

– For LGPD and other privacy laws, stored Brazilian users’ master keys in a specific region with stricter access controls.

– Used per‑region HSM pools for the most sensitive datasets.

Outcome: they significantly limited which teams and systems could see live identifiers, while still operating across multiple clouds and regions.

—

Pro tips and “lifehacks” for professionals

1. Make keys observable, not invisible

Treat keys like any other critical resource:

– Tag them with:

– owner team

– data classification

– rotation policy

– business system

– Set up alerts for:

– unusual decryption spikes

– new principals gaining decrypt permission

– failed decryption attempts

When an incident happens, you want to answer “who decrypted what, when, and from where” without hunting in five different logs.

2. Default‑deny KMS everywhere

In many organizations, KMS policies start permissive and get slowly tightened. Flip that mindset:

– Start with a global deny on decryption for all keys.

– Explicitly allow only:

– specific IAM roles for applications

– break‑glass roles with strong MFA and just‑in‑time approval

This small inversion prevents a lot of “temporary exceptions” that quietly become permanent security holes.

3. Design for key rotation from day one

Key rotation hurts only when it’s an afterthought. Make it a first‑class feature:

– Store the key ID or key version alongside encrypted blobs.

– Implement APIs that can:

– decrypt with any allowed old key

– re‑encrypt with the current key in background jobs

– Define rotation triggers:

– time‑based (e.g., every 6–12 months)

– event‑based (suspected key exposure, change in threat model)

Once this is baked into your architecture, rotation becomes routine rather than a fire drill.

4. Split responsibilities, not just permissions

For high‑sensitivity environments:

– Separate:

– People who manage KMS/HSM and keys.

– People who manage databases and applications.

– Neither side alone should be able to:

– decrypt arbitrary data

– bypass logging

– modify both data and audit trails

It’s not just a security control; it also helps during audits and investigations because there’s no single “super‑admin of everything”.

—

Pulling it together: a practical blueprint

For a typical cloud‑native company handling customer PII and some payment data, a realistic blueprint looks like this:

– At the infrastructure layer:

– Enable encryption at rest everywhere.

– Use cloud KMS integrated with storage, databases, and queues.

– For ultra‑sensitive datasets, back keys with HSM and restrict to specific regions/accounts.

– At the application layer:

– Use envelope encryption with per‑tenant or per‑dataset data keys.

– Employ tokenization for high‑risk fields (national IDs, card numbers, phone, recovery email).

– Implement schema‑driven redaction in logs and traces.

– At the governance layer:

– Maintain a live data inventory: where each type of sensitive data is, and which keys protect it.

– Align key policies with legal and regulatory requirements (LGPD, GDPR, PCI, HIPAA as applicable).

– Regularly test your incident response: simulate key compromise, token vault compromise, and vendor breaches.

When you treat encryption, tokenization and KMS/HSM as a single, coherent system rather than scattered features, proteção de dados sensíveis em cloud stops being a half‑kept promise in a sales deck and becomes an actual, measurable property of your platform.