Why risk-based cloud security policies are different (and why you should care)

When teams migrate from data centers to cloud, most people try to copy old firewall rules and compliance checklists and call it done. That usually fails within months, because cloud workloads are dynamic, short‑lived and heavily automated. A policy that made sense for a static VM farm becomes either impossible to maintain or so restrictive that engineers start bypassing it. That is exactly where segurança em nuvem baseada em riscos para workloads comes in: instead of treating every resource as equally dangerous, you tie controls directly to the risk level of the data, the business process and the threat landscape. In a nutshell, a low‑risk dev prototype shouldn’t be governed like a production payment system, and your policies should reflect that asymmetry from day one.

Key concepts: getting terminology straight before you model anything

Before you start creating policies or diagrams, it helps to pin down a few working definitions in simple, non‑academic language. A “workload” in cloud is any combination of compute, storage, networking and platform services that together deliver a business function: a containerized API, a serverless data pipeline, a legacy VM running SAP in IaaS. A “risk‑based policy” is a rule or expectation (technical or procedural) that is activated and tuned according to the level of risk a workload presents, not just according to its type or environment. “Risk” itself is the intersection of three factors: the impact if something goes wrong, the likelihood of someone exploiting that weakness, and the exposure of that asset. Finally, “data classification” is the structured process of labeling data by sensitivity (for instance, public, internal, confidential, highly confidential) and using those labels to drive technical enforcement, instead of using tribal knowledge and guesswork.

From theory to practice: a simple mental model and a text diagram

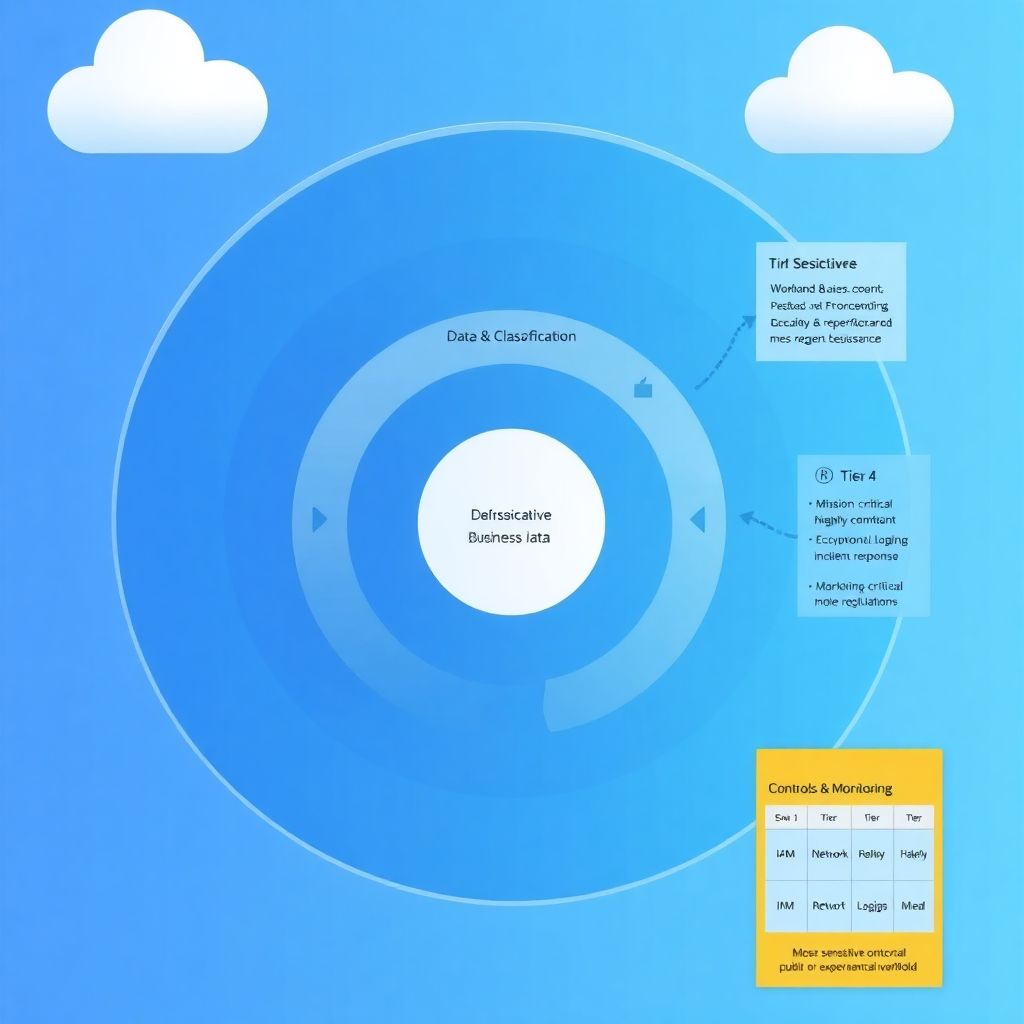

To keep things practical, imagine your cloud security model as three concentric layers that reinforce each other. At the core sits data classification, which tells you what you are actually protecting. Around it sits workload context: which account, which region, which business unit, which compliance obligations. The outer ring is the control layer: IAM policies, network segmentation, encryption, monitoring and response. If you need a text diagram to visualize it, think in terms of: (Diagram: three circles, smallest labeled “Data & Classification”, middle labeled “Workload & Business Context”, outer labeled “Controls & Monitoring”; arrows flowing from inner to outer show that more sensitive data forces stronger controls). This is the mental picture you’ll keep coming back to when building gestão de riscos e conformidade para workloads em cloud.

Case 1: the fintech startup that drowned in permissions

Take a real‑world scenario from a European fintech I worked with. They were born in the cloud, heavily invested in microservices and Kubernetes, but their security posture was classic enterprise: one monolithic “production policy” applied everywhere, for every cluster and every namespace. That meant that an internal analytics tool had the same approval workflow and firewall exceptions as the payment processing engine. Engineers complained that it took days to open a port or add a S3 bucket, and security teams were overwhelmed by exception requests. Incidents weren’t huge, but friction was. When we reframed their approach around risk, the first step was re‑classifying data assets: settlement files, cardholder data and KYC documents went to the top tier; logs and pseudonymized dashboards went to a lower tier. The policy engine then attached stricter network and identity controls only to services touching top‑tier data, leaving internal workloads with simpler default‑deny but easier exception paths.

Defining risk levels and linking them to data classification

To move from intuition to something enforceable, you need crisp definitions of risk levels that developers and auditors can understand without reading a 90‑page PDF. One workable pattern is to create 3–4 tiers that blend data classification with business impact. For example, Tier 1 could be “Mission‑critical workloads handling highly confidential data or regulated information”, Tier 2 “Important workloads handling confidential but not regulated data”, Tier 3 “Internal tools with low business impact”, and Tier 4 “Public or experimental workloads with no sensitive data”. Each tier then inherits baseline requirements for identity, network, logging and backup. That is where como implementar políticas de segurança em cloud para classificação de dados becomes tangible: the label on a dataset or database directly triggers a template of controls in Terraform, CloudFormation or your policy‑as‑code engine, rather than being just a tag that no one uses.

Diagram: mapping risk tiers to concrete cloud controls

Think of a simple horizontal diagram that maps tiers to example controls: (Diagram: four columns labeled Tier 1 to Tier 4; rows labeled “IAM”, “Network”, “Encryption”, “Monitoring”; each cell lists the strictness, like “Tier 1: MFA required for all admins, just‑in‑time access, private subnets only, customer‑managed keys, full packet logs” versus “Tier 4: standard IAM groups, internet‑facing allowed with WAF, provider‑managed keys, basic metrics only”). You don’t have to implement this as a literal matrix, but it helps drive conversations with stakeholders and make risk trade‑offs explicit instead of implicit.

How cloud risk‑based policies differ from traditional on‑premise security

On‑premise environments typically rely on static perimeters and manual change control: firewalls are reconfigured monthly, VLANs are carved up by network teams, and it is assumed that most assets live for years. Cloud, by contrast, encourages ephemeral workloads that might spin up and disappear in minutes, wide use of managed services with shared responsibility, and identity‑driven access as the primary perimeter. As a result, copying traditional network‑centric approaches misses the point. The comparison is sharp: legacy security fixes a strong outer wall and hopes everything inside is safe, whereas a cloud‑native, risk‑based model focuses on every workload having its own “micro‑perimeter” anchored in data sensitivity, not location. Even compliance checks shift from annual audits to continuous controls that are evaluated every time infrastructure code is applied. This is also why ferramentas para classificação de dados e segurança em nuvem corporativa evolved to integrate directly into CI/CD pipelines instead of acting only as periodic scanners.

Step‑by‑step: modeling risk‑based policies for cloud workloads

Let’s break down a concrete, implementable sequence of steps that you can adapt to your own context, without turning it into another theoretical framework that no one reads:

1. Identify and classify data across workloads

2. Map business processes and compliance drivers

3. Define risk tiers and their baseline controls

4. Implement policies as code in cloud accounts and pipelines

5. Deploy monitoring and incident response aligned with tiers

6. Iterate with feedback from developers and real incidents

Each of these steps may involve several teams, but keeping the order helps avoid common traps like trying to buy tooling before you understand your data, or writing policy documents that cannot be automated.

Step 1: discovering and classifying data in the cloud

Most organizations underestimate how scattered their data is. They might know about the main production database but completely forget S3 buckets with ad‑hoc exports, managed service snapshots, or data lakes in secondary regions. To get a reliable map, you typically combine three sources: cloud inventory (listing all databases, buckets, storage accounts), application owners providing context, and automated scanners that look for patterns like PII, PCI or health data. The end goal is not perfect classification, but a usable 80/20 map where you know where the truly sensitive stuff lives. In a practical sense, como implementar políticas de segurança em cloud para classificação de dados means using labels or tags like “data_sensitivity=high” together with resource‑level metadata, and then enforcing guardrails that check those tags during deployment, not six months later in an audit.

Case 2: a retailer’s S3 bucket that almost went public

A global retailer had an analytics team sharing reports using an S3 static website. One engineer accidentally reused a Terraform module and created a bucket with a near‑public policy for a folder that also stored partial customer records. The only reason it was caught before exposure was that their cloud security tool flagged any new bucket with “sensitivity=high” tag and a public ACL as a critical issue. They had recently rolled out automated classification that tagged any dataset with email addresses or payment tokens as “high”, feeding directly into the IaC validation step. Without that tie between classification and enforcement, the misconfiguration would likely have gone unnoticed and become another headline.

Step 2: connecting workloads to business and compliance context

Once you know where sensitive data sits, the next layer is understanding why each workload exists and which obligations it carries. Not all workloads with personal data are equal; a marketing personalization engine may be governed by privacy policies, while a payments ledger may be constrained by both PCI DSS and financial regulations. This is where collaboration with legal, risk and product teams becomes essential. For every critical workload, you want a concise profile: which business capability it supports, which SLAs it has, what downtime costs per hour, and which regulations apply. This profile later drives prioritization: you might decide that a Tier 1 regulated payment engine gets full packet capture, strict egress control and 24/7 on‑call coverage, whereas an internal reporting tool with the same data classification but lower impact might receive lighter‑weight monitoring.

Step 3: defining risk tiers and policy baselines

With data and context mapped, you can define risk tiers in language that both engineers and auditors can live with. The trick is to avoid exploding into a dozen categories that are impossible to remember. Keep it small and opinionated. For each tier, establish a baseline in terms of identity, network, data protection and observability. For example, Tier 1 might mandate private subnets, zero inbound from the internet, strong authentication, least‑privilege IAM roles, customer‑managed keys, backups in multiple regions, and real‑time anomaly detection. Tier 3 could allow internet‑facing services with web application firewalls, managed keys, and daily log shipping instead of streaming. The art in gestão de riscos e conformidade para workloads em cloud is deciding where to place each workload and documenting the rationale, so later exceptions are transparent rather than political.

Comparison: risk‑based vs “one size fits all” cloud security

If you compare this tiered model to a flat security policy where “all production must use X, Y, Z controls”, a few differences stand out. First, risk‑based models handle growth better; as your number of workloads triples, you still have only a few tiers, not a bespoke rulebook per microservice. Second, they enable smarter trade‑offs: you can justify heavier investment in Tier 1 (for instance, deploying expensive behavior‑analytics tooling) because you deliberately spend less on Tier 3 and Tier 4. Third, they provide a language for conversations with the business: instead of arguing about a specific firewall port, you talk about re‑tiering a workload if its impact changes. In contrast, one‑size‑fits‑all approaches tend to drift toward the lowest common denominator, where either everything becomes “critical” and unmanageable, or the policy is silently ignored.

Step 4: implementing policies as code across your clouds

Once you have tiers and baselines, you should resist the urge to document them purely in PDFs or wiki pages. The real power comes from encoding them as reusable building blocks: Terraform modules, CloudFormation stacks, Helm charts, organizational policies in AWS Organizations, Azure Policy or Google Organization Policy. The idea is that when someone provisions a “Tier 1 database”, they are actually instantiating a module that already includes encryption, logging, restricted access patterns and backup schedules that match that tier. You can also integrate policy‑as‑code tools like Open Policy Agent or cloud‑native rules engines that evaluate incoming infrastructure code against your risk‑tier ruleset. That is how you gradually shift enforcement from manual reviews to automated checks, which is vital in fast‑moving environments where dozens of deployments happen daily.

Case 3: tightening a healthcare platform without slowing releases

A digital health platform handling appointment data and limited clinical notes needed to meet stricter privacy regulations in Latin America. Development teams feared that security would mean slower releases. Instead of adding manual approvals, we built “golden templates” for different tiers of workloads and integrated them into their Git repositories. Any new microservice touching patient data had to import the Tier 1 module, which automatically configured VPC peering, private subnets, secrets management and log forwarding. Developers could still deploy several times per day, but the guardrails ensured that core privacy requirements were always met. Over three months, misconfigurations dropped sharply, and security reviews focused on edge cases instead of rechecking basic controls every time.

Step 5: monitoring and melhores práticas de resposta a incidentes em ambientes de nuvem

Risk‑based policy modeling doesn’t stop at prevention; it has to extend into detection and response, or you just end up with a fragile shell. For monitoring, align the depth of visibility with the risk tier. High‑risk workloads should have detailed logs (application, system, and audit), metrics, and where needed, network flow logs and DNS queries shipped to a centralized platform with correlation rules. Lower‑risk workloads can afford summarized metrics and exception‑based logging. When it comes to melhores práticas de resposta a incidentes em ambientes de nuvem, a few patterns are consistently effective: pre‑defined playbooks per tier, automated enrichment of alerts with asset and data classification, the ability to isolate a workload quickly (for example, by cutting off egress or detaching it from load balancers), and rehearsed “game days” where teams practice real‑world failure and attack scenarios.

Diagram: incident response flow for a Tier 1 workload

Imagine a linear flow, but with feedback loops: (Diagram: event occurs → monitoring detects anomaly → alert enriched with workload tier, data sensitivity, business owner → severity auto‑calculated based on tier → on‑call team notified → playbook for that tier executed: isolate resource, snapshot for forensics, block suspicious IAM principals → root cause analysis → update risk model and policy). The key element here is that the tier influences everything from priority to which actions are allowed; for a Tier 4 sandbox, you might just terminate the resource and move on, while for Tier 1 you preserve evidence and involve legal and privacy teams.

Step 6: learning from incidents and adjusting risk models

Risk‑based policies should not be treated as static doctrine. Cloud environments change faster than traditional infrastructure, and actual incidents will always surprise you. Every serious security event or near‑miss is an opportunity to check whether your classification, tiering and controls still reflect reality. For example, if you find that a supposedly low‑risk workload holds cached copies of sensitive data because of a performance optimization, that’s a signal to either retier that workload or change how data flows to it. Similarly, if incident timelines show that you consistently struggle with isolating workloads in a particular environment, you might adjust your baseline to include better segmentation or predefined emergency controls. Over time, this feedback loop makes your gestão de riscos e conformidade para workloads em cloud less about guessing and more about evidence.

Choosing and integrating tools: from classification to corporate cloud security

Tools won’t fix a broken model, but with a reasonably clear risk framework, they can multiply your effectiveness. On the classification side, you can use native cloud discovery services combined with third‑party DLP or data security posture management solutions to scan storage and databases for sensitive patterns, automatically suggesting or applying labels. On the control side, cloud security posture management and workload protection tools can continuously compare deployed resources against your tier‑based baselines, flagging drift or unauthorized changes. For many enterprises, the decisive factor is whether ferramentas para classificação de dados e segurança em nuvem corporativa integrate cleanly with CI/CD and identity platforms, so labels and policies flow from source code to runtime without manual re‑entry. The sweet spot is when your security team curates policies and models, while pipelines and platforms apply them automatically at scale.

Case 4: multi‑cloud chaos to coherent risk posture

Consider a global manufacturing company that ended up with three major cloud providers, several business units, and completely different security practices in each. One BU used Infrastructure as Code heavily, another did everything point‑and‑click in web consoles, and the third outsourced most operations. When they tried to run a company‑wide risk assessment, they realized they couldn’t even answer basic questions like “where is personal data stored?” without weeks of interviews. The turning point came when they defined a small, provider‑agnostic set of risk tiers and associated policies, then mapped native services on each cloud to those tiers. They rolled out classification tooling that applied consistent labels regardless of provider, and wrote organizational policies in each cloud to enforce minimal guardrails. Over a year, the picture went from scattered, anecdotal security to a shared language of risk across clouds, which in turn made it much easier to plan investments and justify priorities to the board.

Practical tips to avoid common pitfalls

A few patterns come up repeatedly when teams attempt this journey. One is over‑engineering the classification scheme with dozens of categories that no one can remember or apply consistently; it’s more effective to start with three or four meaningful levels and refine with experience. Another is pushing all decisions into security, which leads to bottlenecks and limited context. Instead, involve application owners in defining data sensitivity and business impact, while security curates the control templates. A third pitfall is treating policy‑as‑code as “set and forget”; without regular reviews and tests, your modules and rules drift away from actual practices. Building lightweight review cadences, such as quarterly workshops where you review incidents and adjust tiers, helps keep the model grounded in reality. Over time, you’ll notice that conversations shift away from individual tickets toward structural questions about risk tolerance and control coverage.

Bringing it all together: risk as the organizing principle

Modeling security policies around risk for cloud workloads is less about inventing a new framework and more about using risk as the backbone that connects data, workloads, business value and incident handling. When data classification actually drives technical decisions, when workloads sit in clearly defined tiers with matching controls, and when monitoring and response are tuned to those tiers, you move from ad‑hoc, reactive security to a more deliberate posture. It won’t eliminate incidents, but it will make them easier to contain and learn from, while also giving developers enough freedom to ship. In today’s fast‑moving cloud environments, that blend of structure and agility is exactly where segurança em nuvem baseada em riscos para workloads delivers its real value.